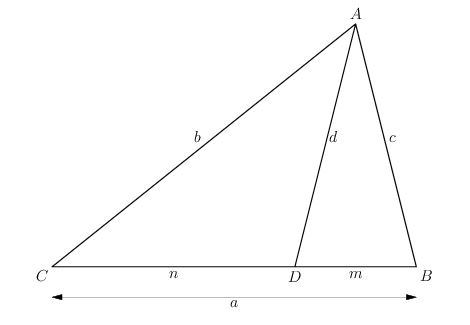

Stewart’s theorem finds the length of a cevian in terms of the side lengths of the triangle

and the lengths

into which point

on

divides that side. Here are some forms of the same formula.

1. The most common form we see is

An easy-to remember form of this is rewriting the above as (a man and his dad hid a bomb in the sink!). This can be proved by applying the cosine rule to triangles ACD and then ABC:

2. If divides the side

in the ratio

,

3. Similar to (2) but substituting ,

This and the previous form are conveniently proved using vectors. Writing the vector ,

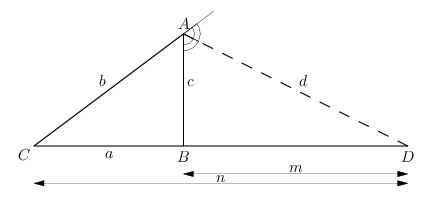

Note that this is valid for any real , so

may lie beyond segment

.

4. Writing (3) as a quadratic in :

5. A symmetric form [1], where the following distances are taken as directed segments ( etc.)

Note that this is equivalent to which is (1).

Here are a few special cases of this formula applying form (3).

(i.e.

:

is the midpoint of

(

):

or

(Apollonius’ theorem)

is a third of the way along

(closer to

) (

):

is the internal angle bisector of

(

):

is the external angle bisector of

(assume

so

):

Leave a comment